The golden age of Italian woodcut illustration began in the last quarter of the fifteenth century and lasted for roughly 100 years, during which period some of the most harmonious and delightful books ever produced issued from Italian presses. The woodcuts designed for these books, in which one can find the graceful refinement of Botticelli, the monumental classicism of Mantegna, the idealized naturalism of Titian, and the mannered elegance of Salviati, are among the most beautiful prints of the Italian Renaissance.

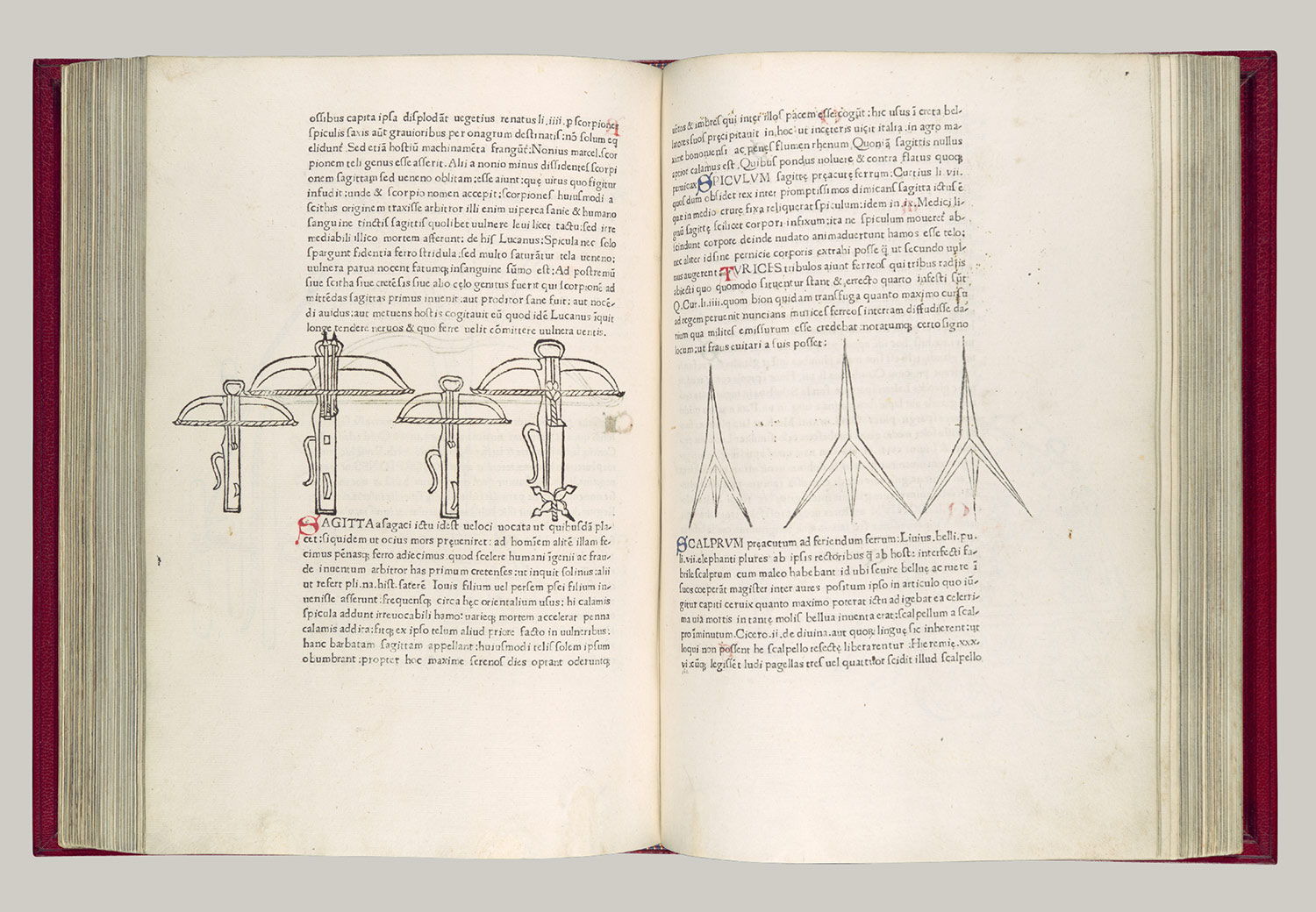

Within a decade of its invention, the printing press had been introduced into Italy by the Germans Conrad Sweynheym and Arnold Pannartz, who in 1464 set up a press at the Benedictine monastery in Subiaco, probably at the invitation of the abbot, Cardinal Turrecremata. This same cardinal was responsible for the first illustrated book published in Italy, his Meditationes de vita Christi, published in Rome in 1467 by Ulrich Han of Vienna (2d ed., 1473; 27.36), in which the thirty bold woodcuts serve as important aids to devout meditation. There has been debate about whether the designer of these woodcuts was Italian or Northern, although most scholars are agreed that the cutter was of Northern origin. In contrast, the spare and elegant woodcuts of the second illustrated book printed in Italy, the De re militari (26.71.4), appear wholly Italian. Published in Verona in 1472, this military treatise contained precise illustrations, notable for their mobile, well-proportioned figures and convincing use of foreshortening, that clarify the descriptions of fortifications and machines of war. Although one of the great advantages of woodcuts is that the blocks could be placed in the same framework as movable type and printed in the same press (for book printing, see 34.30[5]), in this early effort the woodblocks were printed by hand after the text had come from the press.

Related

It was also in Verona that the first illustrated edition of the fables of Aesop was published in 1479 (21.4.3), with woodcuts designed by Liberale da Verona, one of the city's leading painters. While most of the early books printed in Italy were classics intended for humanist scholars—often distinguished by fine presswork and typography, yet rarely illustrated, unless by hand—the collection of tales attributed to the legendary Greek fabulist was intended for a very different audience. Both Latin editions and Italian translations were among the standard texts used to teach students to read. From 1479 forward, the popular character of this moralizing work was enhanced by lively illustrations, none more so than those that appear in the Italian translation by Francesco del Tuppo (31.62.9), which he published in Naples in 1485.

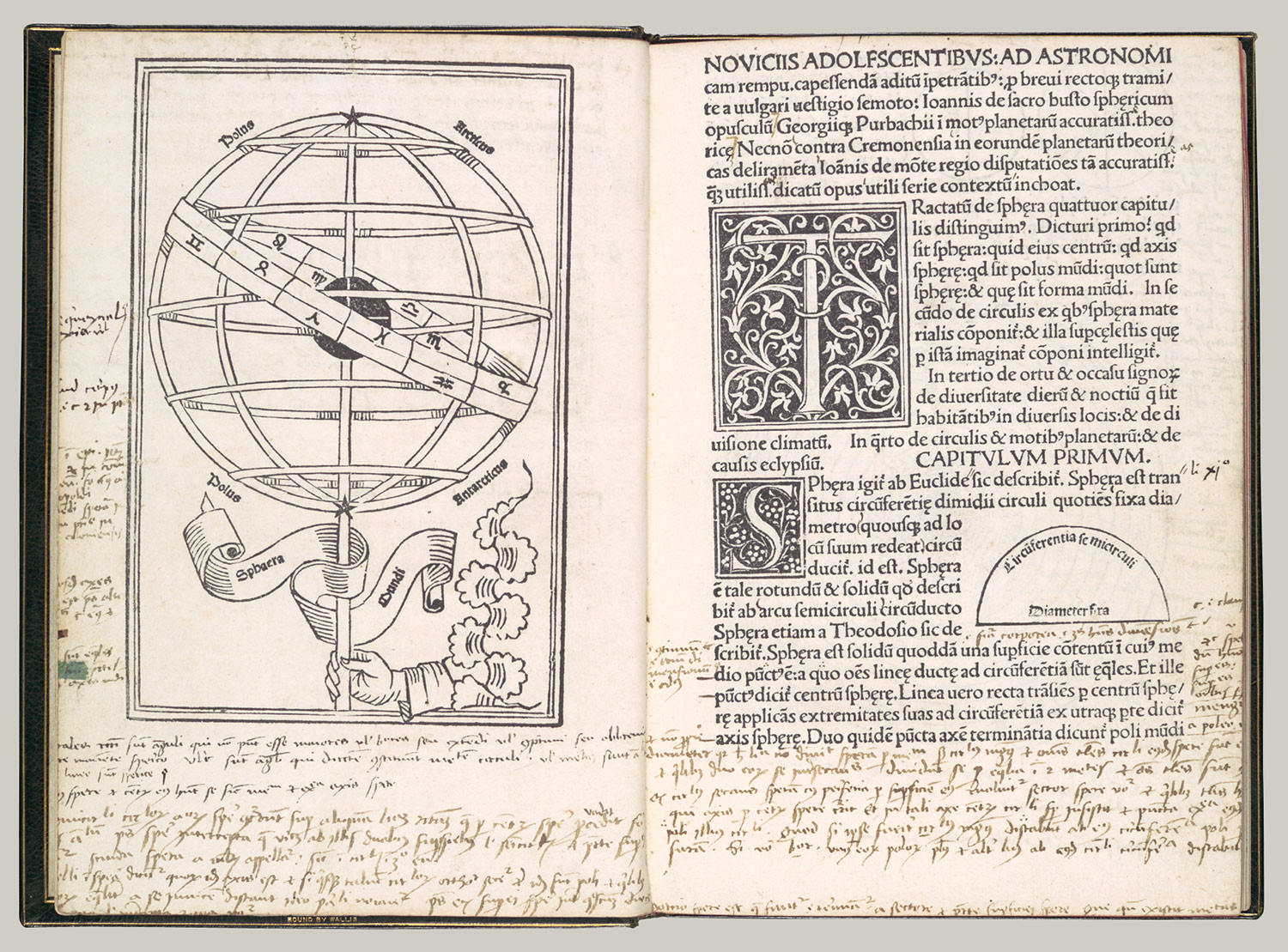

Printing also came early to Venice, where by 1476 the pioneering printer and typographer Erhard Ratdolt of Augsburg had settled and begun publishing. Ratdolt had a particular interest in scientific and mathematical publications, which he made more attractive and often more informative through the addition of ornamental printed initial letters, diagrams, and the use of color printing, all of which are seen in his Sphaera Mundi of 1485 (17.45). Ratdolt was just one of many printers, at first predominantly German, who converged on Venice, where by the end of the century there were more than 150 active presses.

As Venice became the center of international book publishing, its output diversified to include not only the classics in Latin and Greek and treatises on all subjects, but also a great number of devotional texts. Among these, the Devote meditatione sopra la passione del nostro Signore, a work attributed to Pseudo-Bonaventura, was among the most popular, with nearly thirty editions appearing before 1500. The first illustrated edition (33.17), published in Venice in 1487, utilized a set of woodcuts from about a half century earlier. These cuts had previously formed a blockbook, the only known Italian example of this type of publication in which both text and image were printed from blocks of wood. To illustrate the publication of 1487, the inscriptions were trimmed from the bottom of the blocks and the images were accompanied by text printed from movable type.

Timelines (3)

Timelines (3)

No comments:

Post a Comment