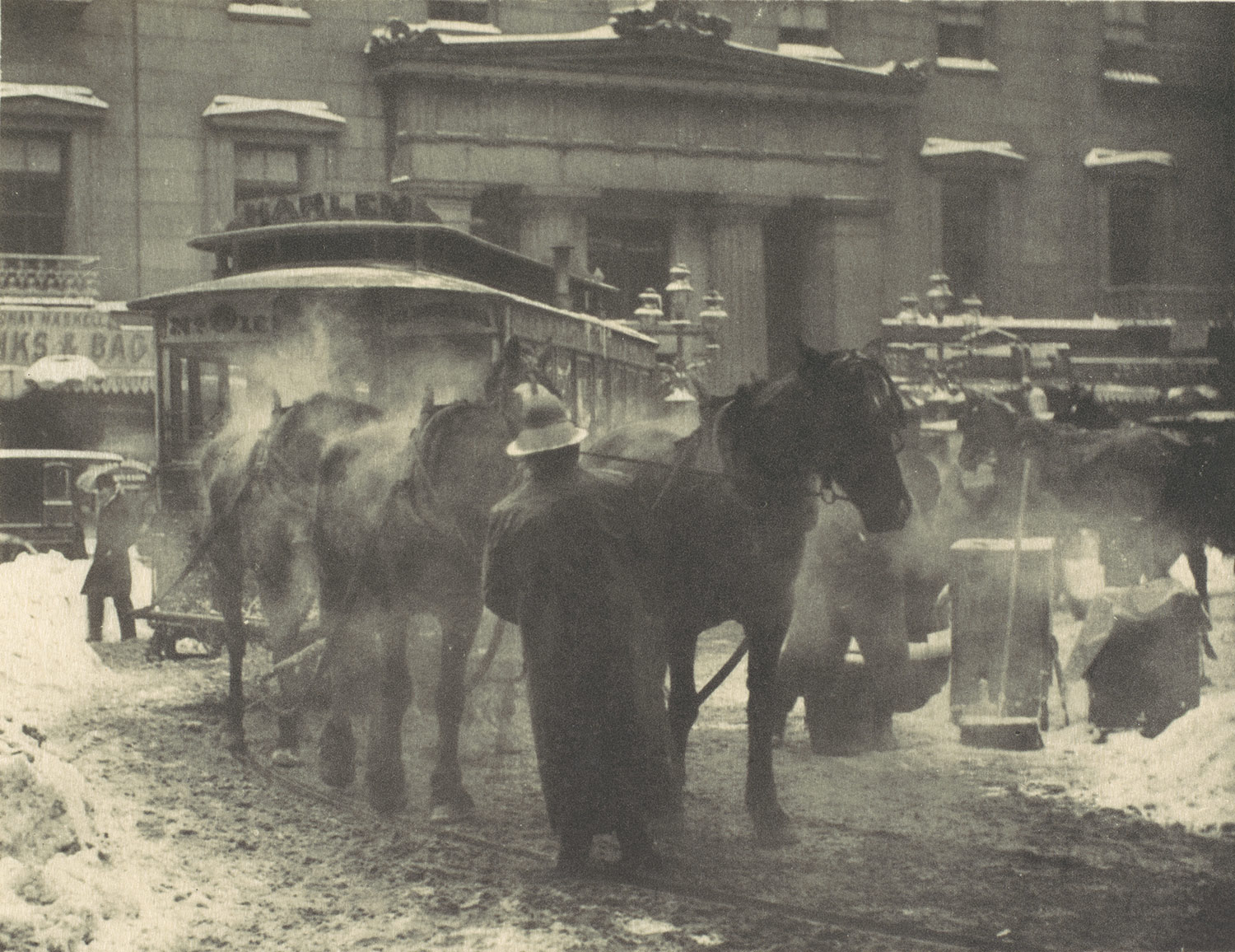

Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1864, and schooled as an engineer in Germany, Alfred Stieglitz returned to New York in 1890 determined to prove that photography was a medium as capable of artistic expression as painting or sculpture. As the editor of Camera Notes, the journal of the Camera Club of New York—an association of amateur photography enthusiasts—Stieglitz espoused his belief in the aesthetic potential of the medium and published work by photographers who shared his conviction. When the rank-and-file membership of the Camera Club began to agitate against his restrictive editorial policies, Stieglitz and several like-minded photographers broke away from the group in 1902 to form the Photo-Secession, which advocated an emphasis on the craftsmanship involved in photography. Most members of the group made extensive use of elaborate, labor-intensive techniques that underscored the role of the photographer's hand in making photographic prints, but Stieglitz favored a slightly different approach in his own work. Although he took great care in producing his prints, often making platinum prints—a process renowned for yielding images with a rich, subtly varied tonal scale—he achieved the desired affiliation with painting through compositional choices and the use of natural elements like rain, snow, and steam (58.577.11) to unify the components of a scene into a visually pleasing pictorial whole.

Related

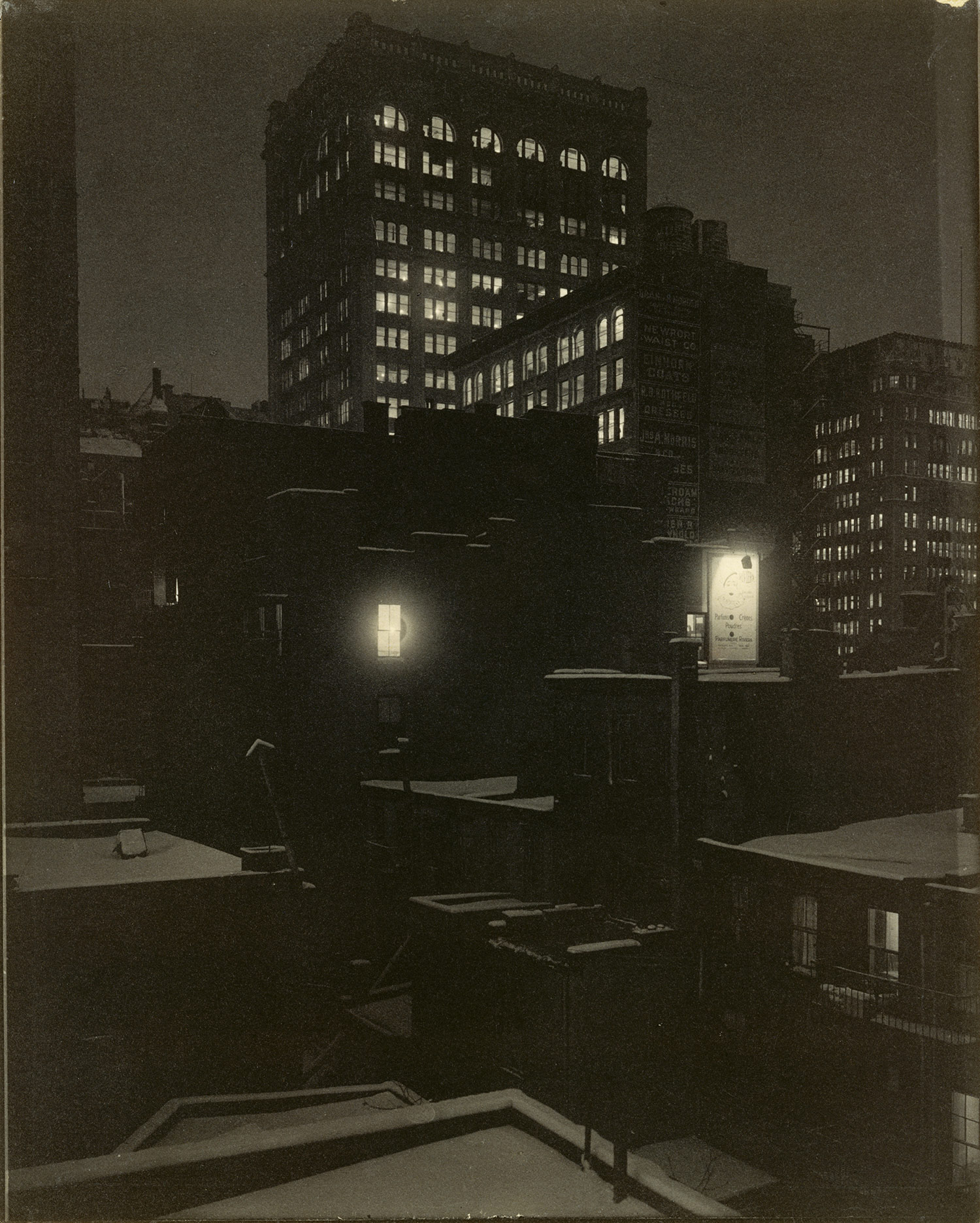

Stieglitz edited the association's luxurious publication Camera Work from 1902 to 1917, and organized exhibitions with the aid of Edward Steichen—who donated studio space that became the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession in 1905, familiarly known as "291" for its address on Fifth Avenue. Through these enterprises, Stieglitz supported photographers and other modern American artists, while also apprising artists of the latest developments in early twentieth-century European modernism (with the help of Steichen's frequent reports from Paris), including the work of Auguste Rodin, Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brancusi, and Francis Picabia. His knowledge of this new kind of art is evident in photographs from these years such as The Steerage (33.43.419), in which the arrangement of shapes and tones belies his familiarity with Cubism, and From the Back Window, 291 (49.55.35), in which Stieglitz's internalization of avant-garde art combines with his own expertise in extracting aesthetic meaning from the urban atmosphere.

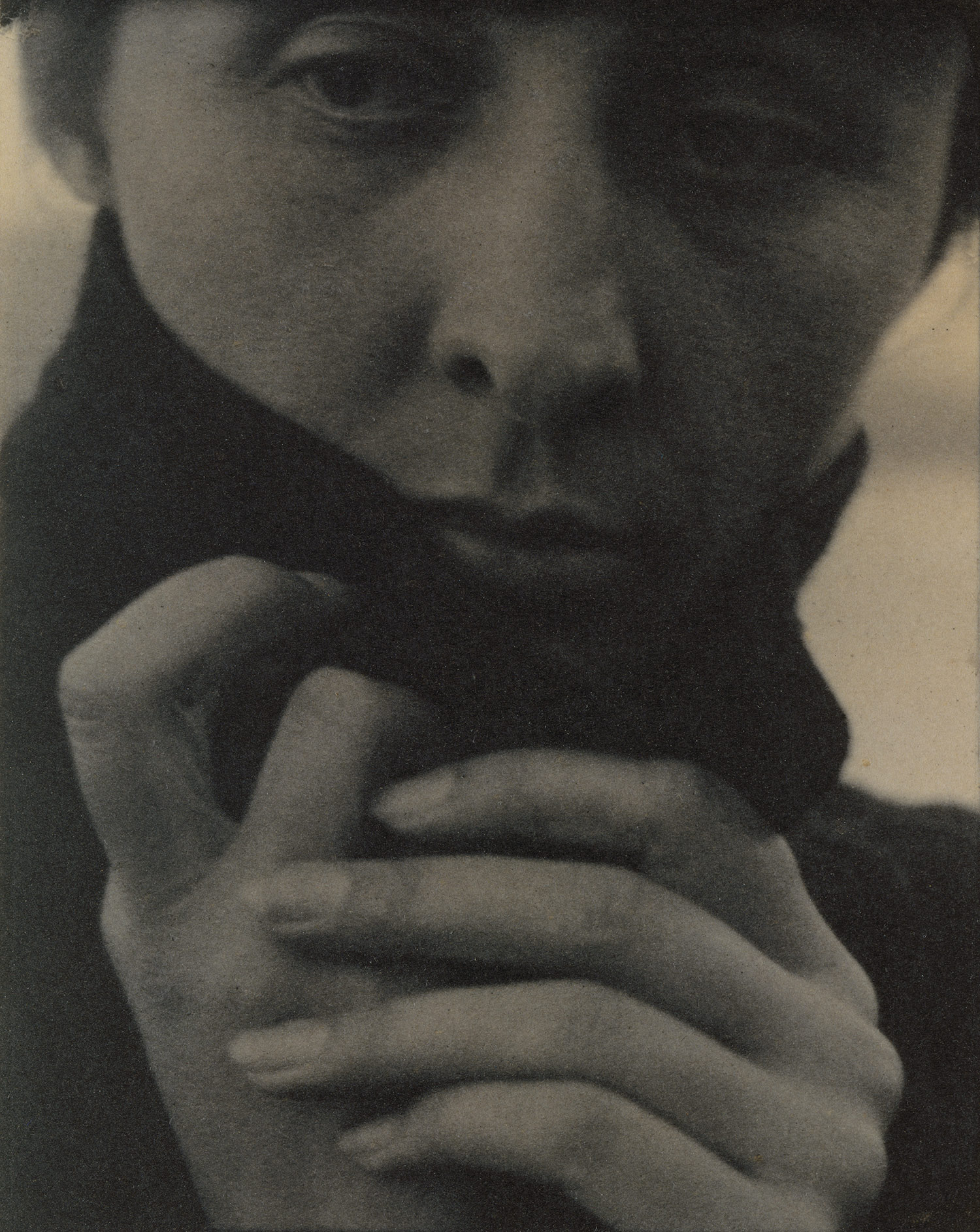

By 1917, Stieglitz's thinking about photography had begun to shift. Whereas, at the turn of the century, the best method for proving the legitimacy of photography as a creative medium seemed to suggest appropriating the appearance of drawing, prints, or watercolor in finished photographic prints, such practices began to seem wrongheaded by the end of World War I. Transparency of means and respect for materials were primary tenets of modern art, which derived meaning from the ephemera of contemporary life. Photography was naturally suited to representing the fast-paced cacophony that increasingly defined modern life, and attempting to cloak the medium's natural strengths by heavily manipulating the final print fell out of favor with Stieglitz and his associates. Stieglitz's support for the photography of Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler crystallized the new approach to the medium, and the change could also be seen in his own photographs. His celebrated portrait of Georgia O'Keeffe (1997.61.19) was one of his chief occupations between 1917 and 1925, during which time he made several hundred photographs of the painter (who became his wife in 1924). His refusal to encapsulate her personality into a single image was consistent with several modernist ideas: the idea of the fragmented sense of self, brought about by the rapid pace of modern life; the idea that a personality, like the outside world, is constantly changing, and may be interrupted but not halted by the intervention of the camera; and, finally, the realization that truth in the modern world is relative and that photographs are as much an expression of the photographer's feelings for the subject as they are a reflection of the subject depicted. Stieglitz's series of photographs of clouds, which he called Equivalents (49.55.29), were made in a similar spirit, embodying this last idea perfectly. The cloud pictures were unmanipulated portraits of the sky that functioned as analogues of Stieglitz's emotional experience at the moment he snapped the shutter.

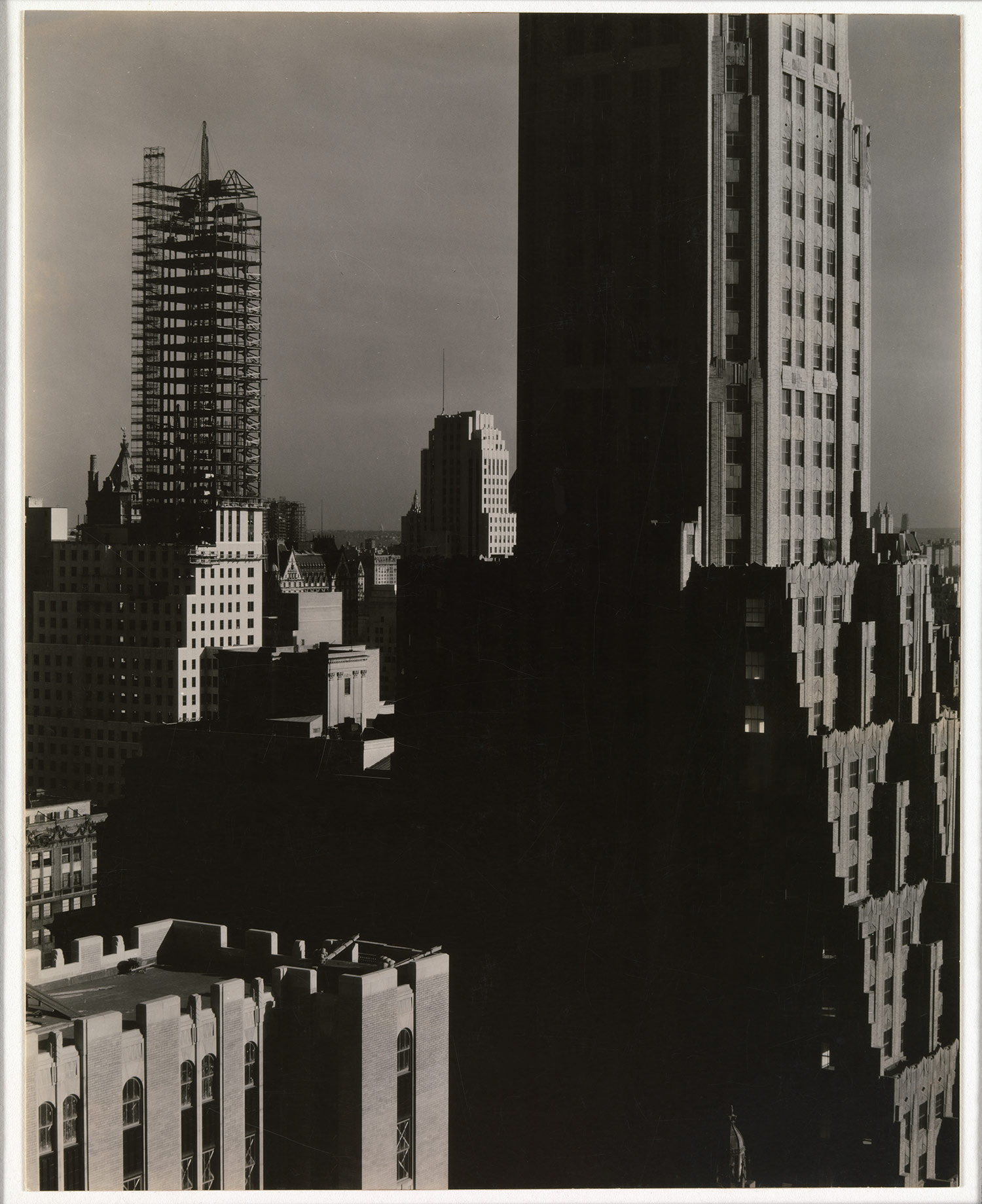

In the final decades of his life, Stieglitz devoted his time chiefly to running his gallery (Anderson Galleries, 1921–25; The Intimate Gallery, 1925–29; An American Place, 1929–46), and he made photographs less and less frequently as his health and energy declined. When he did photograph, he often did so out of the window of his gallery. These final photographs, such as Looking Northwest from the Shelton (1987.1100.11), were impressive achievements that both synthesized the various stages of his photographic development and solidified his position as the most significant figure in American photography. These pictures, virtuoso compositions that emphasize the geometric forms of the city as seen from an upper floor of a modern skyscraper, are also exquisitely constructed and printed and serial in nature, again emphasizing the fragmented nature of contemporary life. Finally, this last series of his career implicitly described his own retreat from the hustle-and-bustle of New York life and embodied the contraction between photography's representative nature and its expressive potential, making them fitting codas in the oeuvre of one of photography's greatest advocates.

Timelines (1)

Timelines (1)

No comments:

Post a Comment